Good grief.

Grief is a river; cold and unrelenting.

Once you’ve slipped in, you can choose to bathe in it and hope for eventual acclimation, or you can leap out of it with a quickness and try to pretend the slip never happened. And while that may seem like the best option in the moment, the water seeping into your shoes and through to your bones will never give your mind and body peace. With the river long behind you, its remnants surround your feet and serve as a frigid reminder of what you’re trying to run away from.

Over the years, I’ve grieved grandparents and friends, relationships and dreams, past versions of myself I’ll never meet again, and future versions that’ll never come to be. I’m nearly 35 and I’ve been in a state of constant grief for more than half of my life. I’ve done it all. I’ve bathed in it, I’ve leapt out of it—hell, I’ve even stared at it before diving in headfirst of my own volition. I’ve been here before. So many times, I’ve been here.

My river changes its curves ever so slightly each time I visit. The surrounding trees look a little different than they used to. Taller, more mature. Two things I had always hoped I’d be. (A girl could dream.)

This river is the home I never asked for.

December 7, 2024. My latest, longest, and most painful visit. The day my sister Sophie passed away. This time, I’m feeling stuck here. But instead of being at the river’s edge, I’ve been clutching the treetops out of fear, hearing the rush of water below yet refusing to acknowledge it with my own eyes.

It’s important to note that it’s not in my nature to be emotionally avoidant, in any sense of the phrase. I’ve been known to wrap myself in emotion with an intensity that knocks me off my feet while encouraging everyone around me to do the same. Because to me, what is humanity and connection without feeling and feeling deeply? I know now, though, what it means to be compelled to do the opposite. To, at best, remain calm. Stoic, even. At worst? Shamefully detached. An extreme deviation from my standard unraveling after a loss.

I have a history of post-loss downward spirals and disorientation, uncontrollable depression and blinding despair. Where each time, and there have been far too many, I find myself back at emotional ground zero, wandering the rubble in search of a stronger foundation before I receive the next call. Now, after almost two decades of one to two unexpected losses each year, more funerals attended than weddings and countless therapists I’ve stunned into silence, I’ve somehow managed to stay standing after the biggest and most feared loss of my life. Sophie. Whether it’s genuine inner strength or simply the fear of losing myself to anguish again, I’ll never know. For now, it’s time to face the water.

In the months leading up to her death, Sophie celebrated her 39th birthday in a party room of the apartment complex she’d been living in for several months. A living situation that gave her the kind of independence in adulthood my family and I always hoped she’d get one day but, given her needs, were never quite sure how it’d happen. It was a miracle, truly. She was living with her best friend and a 24-hour, 7-day rotation of incredible caregivers not five minutes from our parents’ home. Sophie, ever the social butterfly, was in a state of total bliss. Knowing what we would be facing just one month later, I couldn’t be more grateful that she was able to experience that kind of joy and freedom before leaving us.

November 12. What started as a cold turned into a visit to the emergency room. This was becoming more and more common with Sophie over the years. At first, it was every 5 years. Then 3. Then 2. And each visit was nearly identical to the last. In the winter or spring, she would develop a cold. That cold would lead to congestion, which would lead to mucus build-up, which would lead to pneumonia, which would lead to oxygen desaturation, then intubation, infections and, ultimately, disruptions to every one of her major body systems.

And yet, after multiple intubations and what felt like thousands of interventions, Sophie’s color would inevitably come back. Her throat would be freed from the breathing tube. Her voice, hoarse but cheerful, would be heard past the nurses’ station. Laughter would replace the quiet cadence of oxygen support. We’d set her in her wheelchair—a welcome change after weeks of lying motionless in an ICU bed. The dozens of nurses and physicians who’d worked with her during her stay would stare in awe as she rolled out of there like nothing had happened. We’d be trailing behind her with all of our overnight bags, her stuffed animals and Twins pillow, along with mylar balloons and notes of encouragement sent to her from family and friends.

It became a dreaded routine.

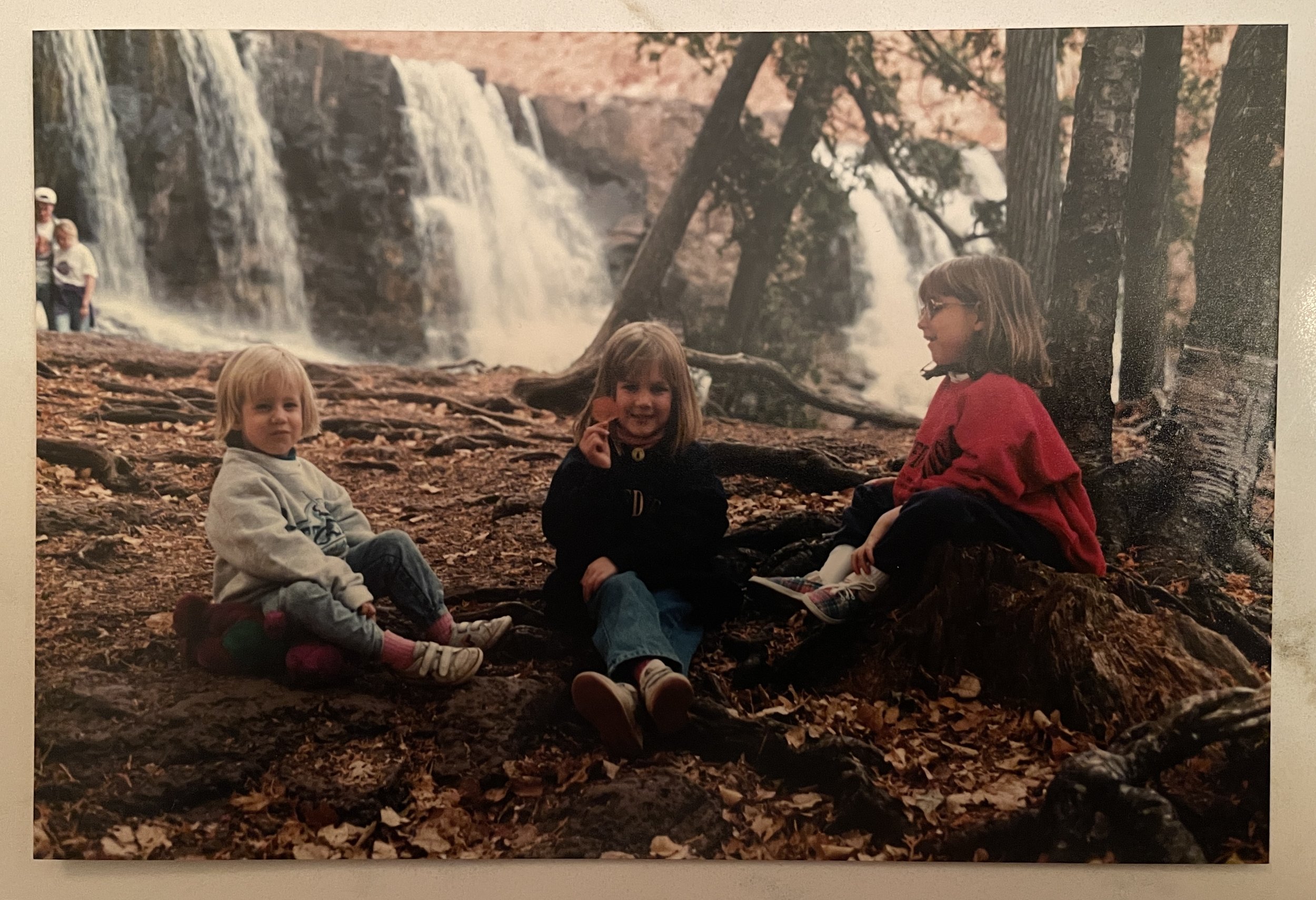

Sophie’s care—emergent or not—was the biggest and most impactful part of our existence. But being the younger two siblings, it was all my other sister Jenna and I knew when it came to functioning as a family unit. We knew the ins and outs of it when we were just kids.

We understood the importance of draining Sophie’s catheter as soon as we got home from school. We often helped with her medications, assisted her in the bathroom, bathed her. We could tell when she was getting infections. We knew every piece of equipment she used from oxygen tanks to bi-pap machines to MIC-KEY gastrostomy tubes. We knew her body as well as we knew our own and we knew what it looked like when something wasn’t right. It could’ve been the slightest drift of her eyes, sudden pallor, or maybe just a backwards lean of her head. We were attuned to it all, always.

Throughout Sophie’s life, we were witness to not one but several of her near-death experiences—the first of which occurred when I was eight years old. Close-call after close-call, a certain hypervigilance took root within me. It hummed quietly in the background of my life when she was in good health and launched itself to the forefront the minute she wasn’t.

That hypervigilance carried me through her hospital stays, and this one was no exception. As was always the case, I knew the minute we stepped foot onto hospital property, we were her advocates, her medical historians and an additional, omnipresent alert system for the staff. For the twenty-five days leading up to her death, we lived on the third floor of the ICU. In the family waiting room, we created makeshift beds using outdated armchairs. In Sophie’s room, Jenna and I crammed ourselves into the corner with our work computers where we did our best to meet deadlines between throat suctioning and conversations with her medical teams. We became experts in that wing of the hospital, as well as familiar faces—not just to the ICU staff but the security personnel, who would already be writing our names on tags as soon as they’d see us enter the corridor.

After spending so much time there, it should come as no surprise that the sounds of her hospital room have been permanently etched into my being. I flinch now at the sound of a carpet being cleaned. The shampooing and the mechanical drawing up of liquid is all too similar to Sophie’s ventilators and the constant suctioning of her throat and lungs. If I close my eyes, I can hear the disturbing cacophony of pulse oximeter alarms and heart monitor warnings. Even something so benign as Brahm’s Lullaby makes my blood run cold. We learned quickly that the first few notes of the lullaby played throughout the hospital each time a new life was brought into this world. Hearing that song, over and over, while seeing Sophie in the state she was in was both beautiful and heartbreaking. It was painful to have to acknowledge repeatedly that families just a couple floors away were experiencing one of the most joyful moments of their lives while tragedy was unfolding for ours.

Sophie. Sweet Sophie. Her exuberance and love of life were juxtaposed with the stillness we saw in these rooms. That stillness wasn’t who she was. She was the embodiment of fun and love and laughter. In spite of her physical limitations, she was action and confidence and adventure. She was the best of us, the brightest of us, the loudest and most loving of us. Outside of the hospital walls, you never would’ve known the fights she put up within them. And she fought hard, through to the very end when it simply became too much for her body.

December 6. That day and into the evening was fraught with extreme emotion—soaring hopes and devastating setbacks. We had oscillated between stability and distress so many times, it was dizzying. We experienced a sort of peace in the morning, then a tragic mishap with her feeding tube in the afternoon. We were able to get her into her wheelchair that evening and when night fell, she went into respiratory arrest. By 11pm, she had been reintubated. With that, a heaviness settled into the room with us. Jenna and I were uncertain about leaving to rest and recuperate before checking back in, but our parents encouraged us to. She was stable enough to get through the night, we’d hoped. Though, there was palpable fear in all of us. Ultimately, Jenna and I agreed that the two of us would go to her house for the night because of its proximity to the hospital, should anything go wrong.

December 7. No sooner did I collapse on her guest bed than my ringtone blared from the phone in my hand. 4:35am. Dad. I shot out of bed with sobering panic. “Did she die?” I was breathless and could barely speak. There was a moment of relief when he said no, but it was fleeting. Through tears, he told me there were some tough decisions to make and within minutes, we were speeding down the freeway in a stupor.

My whole body quivered uncontrollably as I drove. Jenna, who was 6 months pregnant at the time, was doing her best to breathe as the gravity of what we were about to face was closing in on us. This was the experience I’d been fearing my entire life. It was incomprehensible to me that this was it—that this was really happening. By the time I had parked, I was entirely out of body with no recollection of the drive there. Together we hurried to the building, elbows bound and hands woven tightly. It was as if we both knew that if one were to let go, the other would surely give way to the ground. We knew we were walking into this together, just us two. And we knew we were going to walk out of this together, just us two and a memory of her. To have to exist in this life without the wholeness of the three of us is still unfathomable to me.

For the next three hours, we wept as we recalled our favorite memories with her. We laughed through our sobs and broken voices as we told our favorite stories of her antics. We stroked her hair with the same softness she’d often stroke ours. We held her and reminded her of all the things and people and animals she loved most in this world. We drowned in our tears and filled the room with our love for her.

The sun had just begun to spark above the horizon when she took her final breath. With it came an emptiness. A feeling that there really was one less energy, one less person, one less soul in the room with us.

I know that in that moment, we had done everything we could to guide her spirit into the next world and this was her chance to visit all of the people and places that she held so dear. I know she was embracing this newfound freedom from her physical body by soaring. And those of us who knew her know she was soaring at hypersonic speed.

It was her swan song.

I see Sophie every day now.

In every way, in everything. I hear her in music and feel her when I dance. She makes her presence known through colors, and lights, and sparkles. She visits me in my dreams where I hug her and feel her warmth again. Her voice comes to me from every direction to give me guidance. She teases me when I’m clumsy and laughs with me when my heart’s filled with revelry. She holds me up just as Jenna did that night.

This river is the home we never asked for.

Knee-deep but no longer alone; no longer fearing the water. We’re here, finding strength within ourselves and encouraging strength in each other. The three of us together. Elbows bound, hands woven tightly.

This river is home.